Looking for something?

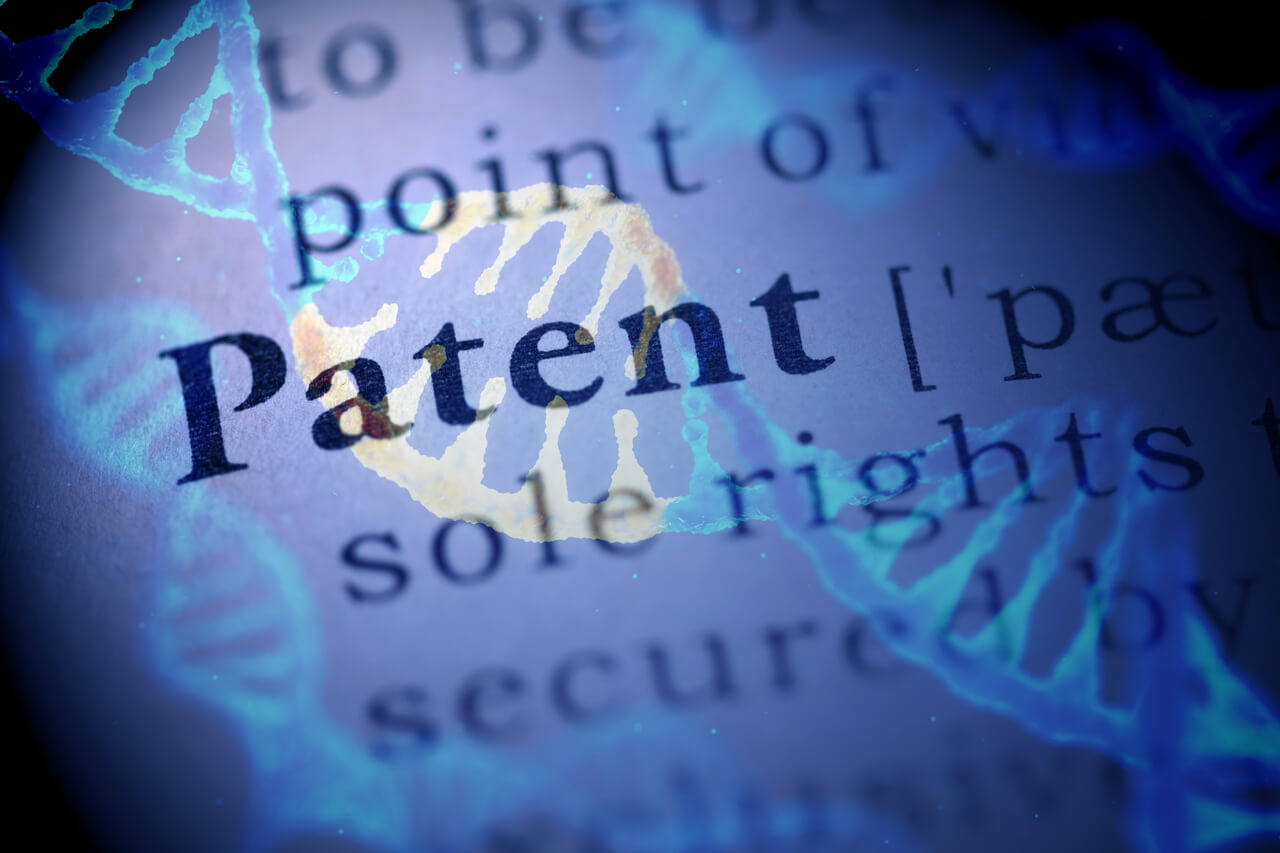

CRISPR Patent Rights and Their Effect on the Industry

A decade ago, Jennifer Doudna of the University of California, Berkley and Emmanuelle Charpentier of the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology drafted blueprints for a groundbreaking gene editing technique. The two scientists had found a way to cut and make precise changes to DNA — a discovery that won them a Nobel Prize. This was the start of CRISPR, a technology that biotech companies now use to develop treatments for genetic conditions like sickle cell disease and inherited blindness (1).

But amidst the scientific breakthrough, a bitter patent war was waged against the two scientists. In 2014, Feng Zhang and his colleagues at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, known collectively as Broad, claimed they were the first to get CRISPR to work in the cells of organisms like yeast, plants, animals, and people (1, 2) — an important step in applying the technology to human medicines and agriculture (3).

In March 2022, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) ruled in Broad’s favor.

A timeline of the technology

The team that passed the “ticker-tape” of getting CRISPR-Cas9 to work in eukaryotic cells depends on a date. Previously, the USPTO awarded patents based on the ‘first to invent system,’ rather than the ‘first to file system.’ This changed in 2013, and the United States now awards patents according to who is first to apply (4).

Doudna and Charpentier originally created a gene editing method that relied on a bacterial enzyme called Cas9 that could turn specific genes on or off and add new DNA to a cell. Although this version of CRISPR worked in test tubes of bacteria, the team initially struggled to translate the technology to animal and human cells. However, they described how CRISPR-Cas9 could edit circular or short linear stretches of DNA in a June 28, 2012, Science paper.

By the fall, October 5 to be precise, Zhang and his colleagues had demonstrated the technology worked in lab experiments and published how it worked in human and mouse cells in an online Science paper on January 3, 2013 (3).

Although Doudna and Charpentier are recognized as the original inventors of CRISPR, patent judges were persuaded by Broad’s claim that Zhang’s lab was working on the same idea simultaneously (3). However, attorney Eldora Ellison representing the University of California, the University of Vienna, and Charpentier — known as CVC — argued that the guide RNA that Doudna and Charpentier described in their June 2012 paper was needed to edit the eukaryotic cells and Zhang’s early success relied on “secret information” he obtained about Doudna and Charpentier’s guide RNA work (3). Broad attorneys challenged this claim, stating that the information was shared publicly at a UC Berkeley conference a week before the Science paper was published (3).

Raymond Nimrod, the Broad attorney, claimed Zhang had CRISPR working on eukaryotic cells as early as July 2012 and had submitted the manuscript to Science by October 5, whereas the CVC scientists achieved this later in October (3). The recent ruling involved looking into lab notebooks and emails to determine which team achieved success first — UPSTO says Broad was first, but potentially only by weeks (4).

In a Science article, Kevin Noonan, a patent attorney, explained that Broad’s argument boils down to “we did it first,” whereas CVC claims this is “not the legal standard for inventorship.”

The University of California, Berkley has created a CRISPR timeline found here.

Biotech companies experience the impact of the patent ruling

Companies that use CRISPR technology and have licensed it from the University of California could be affected by the ruling, however, Broad cannot sue a company until its therapy is approved (4) and although none have reached that stage yet, several are close.

Jacob Sherkow, a law professor at the University of Illinois, said in a Boston Globe article that the patent decision casts a shadow over whether and when the first CRISPR therapies will be launched onto the market (1, 2).

Intellia Therapeutics, CRISPR Therapeutics, ERS Genomics, and Caribou Biosciences all have licenses to use CRISPR-Cas9 methods from the University of California and will likely have to obtain license patents from Broad.

Intellia Therapeutics, a company developing biopharmaceuticals based on CRISPR gene editing, saw its stocks sink 21% following the ruling despite promising data that its therapy decreased a harmful protein by 93% in patients with a deadly liver disease called transthyretin amyloidosis (7). Intellia has also developed a treatment for a genetic form of nerve damage (1). The company said it is reviewing the patent decision, and the outcome would not affect any of its ongoing research and development plans. The statement continued that Intellia is confident CVC will find a path forward to affirm their I.P. rights, including the possibility of an appeal to the Federal Circuit (6).

CRISPR Therapeutics and Vertex Pharmaceuticals plan to file for U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of their experimental sickle-cell disease CRISPR-Cas9 treatment by the end of 2022 (4). The company’s stocks decreased 6% following the ruling. Samarth Kulkarni, CRISPR Therapeutics chief executive, noted that having access to the I.P. is important in the long run, but it hasn’t significantly hindered early-stage innovation (1), a sentiment many researchers in the CRISPR field agree with.

Samantha Zyontz, an economist who studies innovation at Stanford University, noted in the Boston Globe article that the dispute may have helped motivate scientists to discover or design new forms of gene editing that improve or expand on CRISPR-Cas9 — which would exclude it from the patent ruling (1).

However, not all companies using CRISPR are upset by the patent outcome. Editas Medicine, a Cambridge-based biotech firm developing treatments for rare diseases, has an exclusive license with Broad and found its stocks increase by 10% following the ruling.

Meanwhile, the dispute may flow into other forms over CRISPR ownership as Sherlock Biosciences, founded by Zhang and Broad scientists, and Mammoth Biosciences, founded by Doudna and Berkeley scientists, are developing diagnostic tests based on the CRISPR enzymes Cas12 and Cas13, and both claim to have ownership of the technology (1).

The value of Broad’s patents is unknown, but if CRISPR-based therapies are successful, experts believe the royalties could be in the tens of millions of dollars (1).

CRISPR on an international stage

Companies looking to commercialize their CRISPR products globally also face the complex situation that Berkley has won patent disputes with Broad in Europe, setting up what Zyontz describes as a “weird patchwork of global rights” (1).

“You would think that most companies would hedge their bets and just get licenses from both groups, but that isn’t what happened,” she said.

Notably, CRISPR-Cas9 patents in Broad’s portfolio have been disregarded in the European Union due to missing paperwork (4). While finalizing its patents, the Broad team decided to remove one of its inventors from the filings but did so without his approval, a requirement in the E.U. system (4). This means that CVC has a better chance of success in Europe, which makes things interesting from a licensing perspective, noted patent attorney Catherine Coombes, in a Nature article (4).

Additionally, two other companies, ToolGen in Seoul and Sigma-Aldrich in Germany, claim to have invented certain forms of gene editing and are challenging both CVC and the Broad over the CRISPR-Cas9 patent (4).

Future of the dispute

Although a decision has been issued, it’s unlikely the seven-year dispute is over. The CVC has asked the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit to review the USPTO decision (6). However, patent lawyers believe CVC’s chances of success are slim as the court is typically deferential to the patent office’s decisions on complex science cases, explained Noonan (1).

“As long as they didn’t misapply the law, the decision will be upheld,” he added.

What is clear is the ongoing dispute does not help the patients whose lives could change with CRISPR treatments. Although companies with promising therapies for diseases like sickle-cell and liver disease state that the patent outcome does not affect their path forward, it’s unclear how much of a delay obtaining a second license will entail once their therapies are approved. For patients experiencing painful or life-threatening symptoms from their diseases, it likely does not matter who was the first to have the technology work in animal cells; what matters is the timeline of when it will work for them.

References:

- Ryan Cross. Lawyers say the dispute between the Broad Institute and UC Berkeley over who owns the gene editing technique known as CRISPR isn’t over. Boston Globe. April 4, 2022.

- Catherine Shaffer. Broad defeats Berkely CRISPR patent. Nature. March 14, 2022.

- Jon Cohen. New CRISPR patent hearing continues high-stakes legal battle. Science. February 4, 2022.

- Heidi Ledford. Major CRISPR patent decision won’t end tangled dispute. Nature. March 9, 2022.

- Angelica Peebles. CRISPR Ruling Invalidates Some Biotech Company Patents. Time. March 1, 2022.

- Annalee Armstrong. CRISPR patent dispute not over yet as Emmanuelle Charpentier, universities appeal. Fierce Biotech.

- Angelica Peebles. Intellia Therapeutics Sinks as Patent Ruling Overshadows CRISPR Promise. BNN Bloomberg. March 1, 2022.

Disclaimer:

“The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in these articles and highlights are strictly those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Oligonucleotide Therapeutics Society (OTS). OTS takes no responsibility for any errors or omissions in, or for the correctness of, the information contained in these articles. The content of these articles is for the sole purpose of being informative. The content is not and should not be used or relied upon as medical, legal, financial, or other advice. Nothing contained on OTS websites or published articles/highlights is intended by OTS or its employees, affiliates, or information providers to be instructional for medical diagnosis or treatment. It should not be used in place of a visit, call, consultation, or the advice of your physician or other qualified health care provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or qualified health care provider promptly if you have any healthcare-related questions. You should never disregard medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on OTS or an affiliated site.”