Looking for something?

RSV: Developing Vaccines to Protect the Vulnerable

It’s the middle of winter and, at some point during this season, many people will experience a constellation of symptoms that may include coughing, a sore throat, runny nose, headache, body aches, fevers, and fatigue. Most adults would assume they have a cold or the flu, but now, depending on the exact symptoms experienced, this could also indicate that they are carrying RSV or Covid.

Like the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes Covid-19, the respiratory syncytial virus (known as RSV) can also cause severe illness and death in at-risk populations. RSV is the second-highest cause of death in babies aged between one month and one year old, and caused death in more than 101,000 children under the age of 5 in 2019 (1). Recent research is showing that some adults are also at risk, with nearly 6,500 adults dying each year in the US alone and those over 65 experience the highest rates of death.

RSV – Common, Contagious, and Sometimes Deadly

RSV is so common that most children will have the infection by their second birthday – and an individual can be infected more than once. It spreads easily via direct contact or through the air (someone merely needs to cough or sneeze near you to transmit the virus). The virus can live on hard objects for hours, and touching the object then touching your nose, mouth, or eyes is enough to become infected. To make protecting yourself and your loved ones even more difficult, some people can be contagious for as long as four weeks after their symptoms disappear (2).

RSV usually lasts a week or two and causes mild symptoms similar to the common cold, including a runny nose and/or congestion, sneezing, a sore throat, headache, a low-grade fever, and a dry cough. It may also cause bronchiolitis (inflammation and congestion in the bronchioles, which are the small airways of the lungs) and pneumonia (infection causing inflammation and fluid buildup in the air sacs of the lungs) (2).

More serious RSV infections may be indicated by symptoms that include a fever, severe cough, wheezing, rapid or difficult breathing, and a blueish color to the skin that is caused by a lack of oxygen (2).

In babies, a severe RSV infection will often produce symptoms that include shallow, rapid breathing, irritability, cough, poor feeding, lethargy, and it may even be so difficult for the baby to breathe that their chest muscles and skin visibly pull inward with each breath (2).

Adults, especially those over 60, can experience complications that include bronchitis, pneumonia, hospitalization, and death. It can also result in a long-term decline of respiratory function and exacerbate underlying medical conditions such as COPD and asthma.

Two Paths to Prevention – Vaccines and Monoclonal Antibodies

As most know, a vaccine is a substance that trains your body to recognize a virus or other foreign invader and learn how to mount a defense against it, so that the immune system will recognize that particular antigen in the future. During this process, the immune system creates proteins called antibodies that recognize the specific antigen. Then, when an antibody encounters the antigen in the future, it kills, immobilizes, or targets the antigen for destruction. In the case of a virus, antibodies prevent the virus from attaching to or entering your cells.

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are not the same as vaccines. Once a person’s immune system creates antibodies (either from an infection or vaccination), the antibodies can be replicated in a lab and given to other people to prevent or treat the infection. Once received, monoclonal antibodies work in the same way that your body’s natural antibodies would. mAbs do not last as long as antibodies naturally produced but are highly valuable for their ability to benefit people who do not develop or maintain an immune response. Infants, whose immune systems are not yet developed, also benefit from monoclonal antibodies.

RSV Vaccinations and a Deadly Beginning

In the 1960s, an unsuccessful formalin-inactivated RSV vaccine was developed, but unfortunately, it caused a severe lung inflammatory response during the first natural RSV infection after vaccination and resulted in two deaths (3). This response was termed “enhanced RSV disease” (ERD), and it hindered the development of other RSV vaccines for many decades (3).

The necessity of finding a solution for RSV was not ignored in the intervening years. A monoclonal antibody called palivizumab (Synagis) that attaches to the F protein on the surface of RSV was developed. Palivizumab reduces the risk of hospitalization due to RSV, and at-risk babies receive monthly injections during RSV season (4). In 1998, it was approved by the FDA for use in high-risk infants and children under the age of two and was approved by the EMA the following year.

However, attempts to create a vaccine were unsuccessful. For many years, teams targeted the wrong proteins, or incorrect forms of the F protein (5). Then in 2013, Jason McLellan et. al published a paper describing a way to stabilize the F protein of RSV in its prefusion form (6). This is significant because, like the spike protein on SARS-CoV-2, the F protein on RSV allows the virus to fuse with cells and infect them. The stabilization keeps the protein folded in the prefusion shape, exposing key antibody target sites (5), and providing an important piece of the puzzle in creating effective vaccines.

In recent years, technological advances and greater knowledge of both the biology of RSV and the pathogenesis of ERD provided enough confidence to begin attempting to create a safe and effective vaccine for this disease that carries such great risk for infants and elderly adults.

Barney Graham, who led the team that designed the molecular strategy to lock the F protein in the prefusion configuration, stated that in addition to saving lives, “the bigger goal is to improve overall lung health of infants. If they’re infected with RSV very early in life and develop severe disease, that affects their lung development and overall lung health probably for their lifetime.”

Vaccines for infants pose a problem, as babies’ immature immune systems do not produce a great response to many vaccines during their first two months after birth, which is the most critical time in an infant’s likelihood of developing a severe RSV infection. Thus, vaccinating pregnant women is another avenue being explored, as it generates maternal antibodies, which then travel through the placenta to reach the fetus (and through breast milk after birth), providing protection during those first crucial months (5).

Barney Graham explained that “The elderly have been infected so many times with RSV already that they’re already primed. So you’re really just boosting them with the vaccine, and that’s safe. The same is true of the maternal immunization.”

Both vaccines and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are being explored to protect infants and at-risk adults from the dangerous effects of RSV.

Thus, the World Health Organization (WHO) convened a group of regulatory experts to develop guidelines regarding the quality, safety, and efficacy of RSV vaccines. The guidelines, which encompass live-attenuated vaccines, protein-based vaccines, nucleic acid vaccines, and vaccines produced using recombinant viral and other vectored systems can be found here.

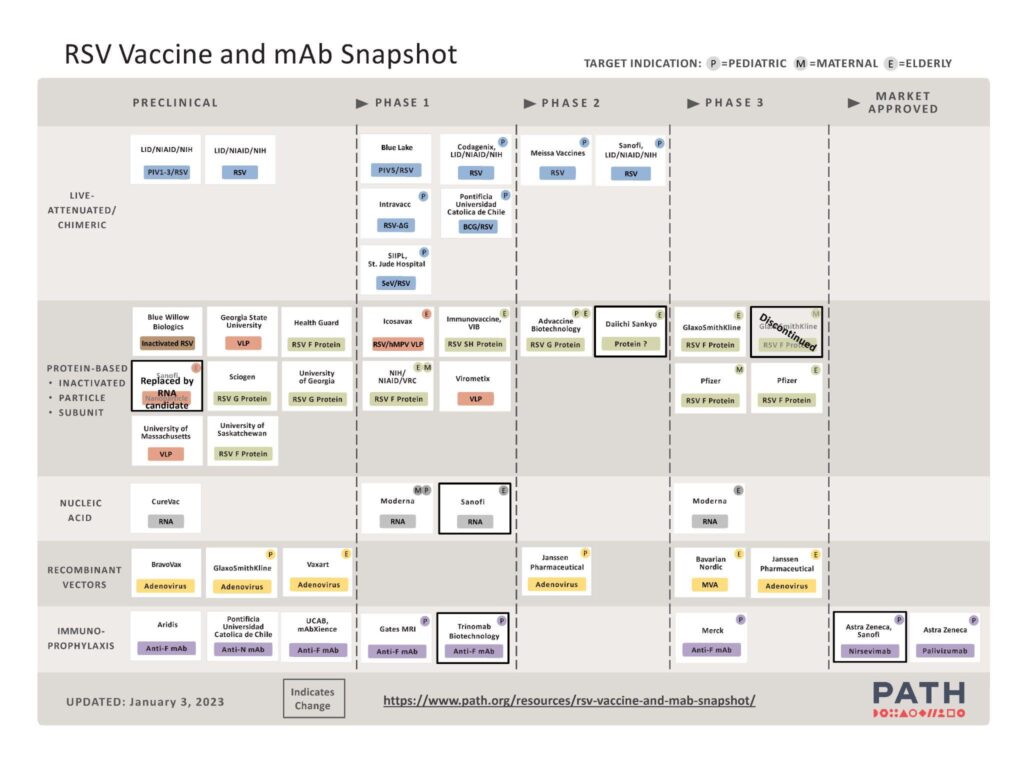

PATH tracks and updates the global RSV vaccine development pipeline. As you can see from the image below, there are a significant number of RSV vaccines and mAbs in clinical trials or preclinical development.

(https://www.path.org/resources/rsv-vaccine-and-mab-snapshot)

For an in-depth explanation of the various types of vaccines being studied for RSV, as well as their advantages and disadvantages, see this review. Here we will briefly outline candidates that have received approval or are in Phase 3 clinical trials.

Astra Zeneca developed palivizumab (Synagis), the monoclonal antibody mentioned above that has been approved for use in high-risk infants, and it was the only option available for over two decades.

Astra Zeneca and Sanofi have recently developed a long-acting antibody called nirsevimab (Beyfortus) that also attaches to the F protein on the surface of RSV. It has been shown to effectively reduce lower respiratory tract disease (including bronchitis and pneumonia) caused by RSV that requires medical attention in infants. In contrast to palivizumab, nirsevimab is only administered once to infants and young children via an injection into the thigh muscle.

Beyfortus received approval from the European Medicine Agency for use in the European Union on October 31, 2022. Submission to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was recently accepted for review, with a target decision date of the third quarter of 2023.

Janssen has developed an adenovirus 26 vector RSV vaccine that combines Ad26.RSV.preF with a prefusion F (preF) protein (Ad26.RSV.preF). In a phase 2b trial that included 5,782 adults 65 years or older, this vaccine has proven to be up to 80% effective in preventing severe lower respiratory tract infection and 70% effective against any symptomatic RSV-associated acute respiratory infection. The trial has only covered one season, and participants will be tracked for another season to determine how long efficacy lasts.

The phase 3 study will include approximately 23,000 adults 60 years and older, and will evaluate the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the vaccine.

The vaccine is also being tested in adults 18-50 years old and children 12-24 months. In the phase 1/2a trial, the candidate elicited humoral and cellular immune responses in adults and RSV-seropositive children, was well tolerated, and there were no serious adverse events (7).

Moderna has developed an mRNA vaccine candidate for RSV. Interestingly, Moderna’s mRNA-based RSV vaccine was already in development when SARS-CoV-2 became a global health concern, allowing them to swiftly pivot the technology to provide a vaccine during the pandemic (5). The vaccine contains a single mRNA sequence encoding for the stabilized prefusion F glycoprotein and uses the same lipid nanoparticles that Moderna used in the Covid-19 vaccine. In the same way that the mRNA Covid vaccine causes the body to create the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, the mRNA sequence in Moderna’s RSV vaccine, MRNA-1345, stimulates production of the stabilized prefusion F protein.

In a phase 3 trial encompassing approximately 37,000 adults 60 years or older in 22 countries, MRNA-1345 was 83.7% effective in preventing RSV lower tract respiratory disease (defined by two or more symptoms) in older adults. MRNA-1345 was generally well-tolerated with no safety concerns, and the most common side effects were pain at the injection site, headache, and fatigue. As myocarditis was a rare complication of the mRNA Covid vaccines, it was closely monitored, and there have been no myocarditis concerns thus far. Based on these excellent results, Moderna intends to submit its candidate for regulatory approval globally this year. mRNA-1345 is being tested in pediatric populations, and trials are planned for pregnant women to determine whether infants will gain protection.

Pfizer has developed a bivalent RSV vaccine (RSVpreF or PF-06928316) in which synthetic versions of the stabilized preF protein are injected directly. In a phase 3 trial investigating safety and efficacy in approximately 37,000 adults 60 years and older, it was found that a single injection was 85.7% effective at preventing severe disease (defined by three or more symptoms) due to RSV-associated lower respiratory tract illness (LRTI-RSV) and 66.7% effective in providing protection against LRTI-RSV defined by two or more symptoms. The vaccine was well-tolerated in older adults with no safety concerns.

Pfizer recently announced excellent results from their phase 3 maternal trial that included approximately 7,400 pregnant individuals. Results showed that pregnant women who received the vaccine did indeed transfer protection to the baby, as infants born to these women were substantially less likely to develop RSV infections that required clinical intervention in their first few months. In the first 90 days after birth, the vaccine was 81.8% effective in preventing severe lower respiratory tract illness requiring medical attention, and 69.4% effective in the first 6 months. It was well tolerated, with no safety concerns for the mother or newborn. Infants were followed for 1-2 years to determine safety and efficacy.

Based on the positive trial results, Pfizer filed an application for approval with the FDA in 2022 and will be submitting applications to other regulatory authorities as well.

GSK’s bivalent RSV vaccine also utilizes synthetic versions of the stabilized preF protein. A phase 3 trial that included approximately 25,000 participants determined that the vaccine was highly effective in adults aged 60 and above, demonstrating overall efficacy of 82.6% against severe RSV-LRTD (at least two lower respiratory signs). Encouragingly, vaccine efficacy was 94.6% in participants with pre-existing comorbidities, and 93.8% in adults 70-79 years old. It was safe and well-tolerated, with mild adverse events such as injection site pain, fatigue, myalgia, and headache. The positive results led GSK to file applications for approval with the European Medicines Agency, Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and the US FDA in 2022.

Bavarian Nordic also has a candidate, MVA-BN RSV, that is based on their proprietary vaccine platform technology in a phase 3 trial with over 20,000 participants who are 60 years or older. The vaccine incorporates five distinct RSV antigens to stimulate a broad immune response against both RSV subtypes (A and B). In the phase 2 trial, MVA-BN RSV demonstrated a vaccine efficacy of up to 79% in preventing symptomatic RSV infections.

Changing the Future

Despite the initial difficulties in creating a safe vaccine, advances in technology and knowledge have provided an opportunity to prevent severe illness and death caused by RSV that, before now, so many infants and elderly people have been vulnerable to. Now, we have not just one but many types of vaccines that are proving to be both safe and effective. Perhaps in the coming years, families will no longer have to worry about losing their loved ones to this virus.

References:

- Li Y, Wang X, Blau DM, Caballero MT, Feikin DR, Gill CJ, Madhi SA, Omer SB, Simões EAF, Campbell H, Pariente AB, Bardach D, Bassat Q, Casalegno JS, Chakhunashvili G, Crawford N, Danilenko D, Do LAH, Echavarria M, Gentile A, Gordon A, Heikkinen T, Huang QS, Jullien S, Krishnan A, Lopez EL, Markić J, Mira-Iglesias A, Moore HC, Moyes J, Mwananyanda L, Nokes DJ, Noordeen F, Obodai E, Palani N, Romero C, Salimi V, Satav A, Seo E, Shchomak Z, Singleton R, Stolyarov K, Stoszek SK, von Gottberg A, Wurzel D, Yoshida LM, Yung CF, Zar HJ; Respiratory Virus Global Epidemiology Network; Nair H; RESCEU investigators. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022 May 28;399(10340):2047-2064. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00478-0. Epub 2022 May 19. PMID: 35598608; PMCID: PMC7613574.

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2021, January 9). Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved February 2, 2023, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/respiratory-syncytial-virus/symptoms-causes/syc-20353098

- Acosta PL, Caballero MT, Polack FP. Brief History and Characterization of Enhanced Respiratory Syncytial Virus Disease. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2015 Dec 16;23(3):189-95. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00609-15. PMID: 26677198; PMCID: PMC4783420.

- 1998. Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants. The IMpact-RSV Study Group. Pediatrics 102:531–537. 114.

- Powell K. The race to make vaccines for a dangerous respiratory virus. Nature. 2021 Dec;600(7889):379-380. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03704-y. PMID: 34893769.

- McLellan JS, Chen M, Leung S, Graepel KW, Du X, Yang Y, Zhou T, Baxa U, Yasuda E, Beaumont T, Kumar A, Modjarrad K, Zheng Z, Zhao M, Xia N, Kwong PD, Graham BS. Structure of RSV fusion glycoprotein trimer bound to a prefusion-specific neutralizing antibody. Science. 2013 May 31;340(6136):1113-7. doi: 10.1126/science.1234914. Epub 2013 Apr 25. PMID: 23618766; PMCID: PMC4459498.

- Stuart ASV, Virta M, Williams K, Seppa I, Hartvickson R, Greenland M, Omoruyi E, Bastian AR, Haazen W, Salisch N, Gymnopoulou E, Callendret B, Faust SN, Snape MD, Heijnen E. Phase 1/2a Safety and Immunogenicity of an Adenovirus 26 Vector Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Vaccine Encoding Prefusion F in Adults 18-50 Years and RSV-Seropositive Children 12-24 Months. J Infect Dis. 2022 Dec 28;227(1):71-82. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac407. PMID: 36259542; PMCID: PMC9796164.

- Drew L. Will a new wave of RSV vaccines stop the dangerous virus? Nature. 2023 Feb;614(7946):20. doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-00212-z. PMID: 36707707.

“The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in these articles and highlights are strictly those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Oligonucleotide Therapeutics Society (OTS). OTS takes no responsibility for any errors or omissions in, or for the correctness of, the information contained in these articles. The content of these articles is for the sole purpose of being informative. The content is not and should not be used or relied upon as medical, legal, financial, or other advice. Nothing contained on OTS websites or published articles/highlights is intended by OTS or its employees, affiliates, or information providers to be instructional for medical diagnosis or treatment. It should not be used in place of a visit, call, consultation, or the advice of your physician or other qualified health care provider. Always seek the advice of your physician or qualified health care provider promptly if you have any healthcare-related questions. You should never disregard medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on OTS or an affiliated site.”